As we covered in a Hemp Market Insider article earlier this month, the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, along with lingering supply chain issues from the COVID-19 pandemic and other factors, are expected to impact hemp production and prices for some time to come. One of the issues affecting hemp are disruptions in global corn and grain supplies, which in turn affects prices and supplies for one of the most common solvents used in hemp cannabinoid oil extraction: ethanol.

Rising prices for ethanol and costs to have it delivered are some of the numerous items impacting the bottom lines of hemp-cannabinoid extractors. Volatility in fuel and shipping markets is also making for challenging times for businesses supplying ethanol to the hemp industry. For perspective on these issues, Hemp Benchmarks spoke with a business that supplies ethanol and other solvents to hemp-CBD processors.

Ethanol Emerges as Hemp-Cannabinoid Industry’s Preferred Solvent

For the past several decades the hemp and cannabis industries have primarily been using petroleum-based hydrocarbons and carbon dioxide (CO2) gas for their extraction processes. However there is another, popular method of extraction that uses alcohol, which has a very long tradition. For centuries, alcohol has been employed widely as a solvent for the creation of tinctures and the extraction of essential oils from a variety of plants.

In this extraction method, hemp is soaked in alcohol, most commonly ethanol. Ethanol is a type of alcohol that is generally produced by fermenting starch or sugar-based plant material, typically corn in the U.S. The solution is later evaporated, leaving behind the cannabinoid-containing oil. Ethanol is considered by many in the hemp sector to be one of the safest, most efficient, and cost-effective methods for the extraction of hemp-CBD and other cannabinoids.

Before the 2018 farm bill legalized hemp nationally, Matthew Geddes, CEO and co-founder of Ohana Chem Co. said most laboratories in the hemp sector used hydrocarbons and CO2 for hemp extraction. According to its website, California-based Ohana is one of the largest solvent suppliers in the nation’s hemp-CBD space, specializing in ethanol, hydrocarbons, and their related logistics.

Geddes noted that many in the hemp industry soon realized ethanol’s efficiency. “For the hemp and CBD industry, people like to focus more on a volume and efficiency level [rather] than more of a terpene quality level,” he added. [Editor’s note: Hydrocarbon extraction, particularly methods employing butane or propane, is considered superior for preserving the terpenes contained in cannabis plant material.] “That’s not for all of our clients, but that’s for a majority of our clients. What we’ve seen in the past three to four years is the industry is now leaning more towards an ethanol-efficient extraction method.”

Rising Prices for Ethanol and its Delivery Impact the Industry

Like any commodity, ethanol prices can fluctuate. In recent years, there has been significant volatility. “Right now [the price of ethanol] is at an all-time high, with what’s going on in the world,” Pono Menor, another co-founder and Executive Vice President of Logistics for Ohana, told Hemp Benchmarks.

Another factor raising the cost of ethanol for hemp processors is elevated shipping costs for all goods, due to continued supply chain disruptions initiated by the coronavirus. Fuel prices have been rising since last year as COVID-related restrictions were lifted, demand increased, and, most recently, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine provided another shock to global energy markets.

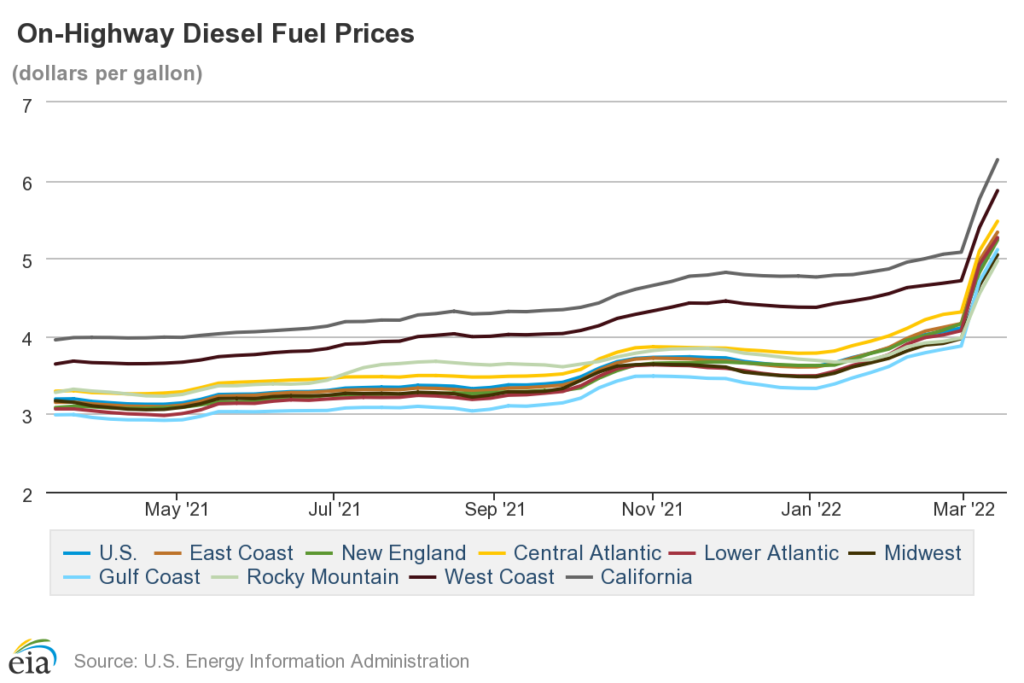

Shippers and carriers in the U.S. typically add a fuel surcharge (FSC) onto the price to transport goods in order to account for the fluctuating cost of fuel. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) collects and publishes retail diesel fuel price data weekly. That data is in turn used by shippers to determine their fuel surcharges. As the chart below shows, retail diesel prices as assessed by EIA have been rising over the last year and spiked even higher recently with the advent of the war in Ukraine, leading shippers to charge higher FSCs.

According to Menor, the FSCs charged by the shippers and carriers Ohana works with have gone up from 13% last year to around 32.5% in mid-March. Those wide swings “make it hard to track our bottom line,” noted Geddes. However, he added, the company is currently working to create a streamlined business model to avoid surprise price increases after delivery to their clients.

Ethanol Suppliers Hope to Lower Costs with Professionalization, Economies of Scale

Geddes noted that starting in early 2019, when ethanol was becoming a mainstream method of extraction, hemp stakeholders often had to work with some rather dubious players. While Ohana is not an ethanol broker, he said, “you still have a lot of [ethanol] brokers … pumping up their prices, forcing hemp companies to go through four or five middlemen before acquiring their product.” Hemp companies now, he added, “are yearning for [a] streamlined process, they need to be more efficient. Their burn rates are astronomical.”

There are other signs that the ethanol side of hemp extraction is becoming more mainstreamed and accepted by corporate America. According to Arnold Stein, Ohana’s Senior Vice President of Sales and another co-founder, the company recently signed a deal with Illinois-based Marquis Energy, which Stein described as the largest dry mill ethanol (ethanol containing no water) plant in the world. The agreement, said Geddes, “gives us the power to have a locked-in price that we are able to guarantee on the back end with our clients, and work with them.”

Geddes believes the older business models for ethanol extraction companies are rapidly fading as the use of ethanol in hemp extraction expands. “It’s becoming more commercialized,” he said. “There’s more demand, there’s more people needing the product; therefore there’s more need for quicker, more efficient streamlined extraction processes.”