While the passage of the 2018 Farm Bill fueled a boom in hemp-derived CBD production in the United States, the domestic market for grain hemp trundled along steadily. Operators in the U.S. grain hemp sector reported relative stability in recent years, compared to the roller-coaster ride experienced by those dealing in hemp for CBD and other cannabinoids.

According to Chad Rosen, the founder and CEO of Victory Hemp Foods – a Kentucky company supplying wholesale food, pet, and skin care ingredients manufactured from hemp seeds to Consumer Packaged Goods (CPG) companies and other businesses – the landscape of the domestic grain hemp market subsequent to the 2018 Farm Bill did not experience a huge shift from the situation on the ground when U.S. hemp production was governed by the 2014 Farm Bill, which first authorized production and marketing of the crop for research purposes. “I don’t know that much realistically changed in terms of markets opening, increased acreage,” Rosen told Hemp Benchmarks in an October interview.

Part of the reason for the relative steadiness in the domestic grain hemp market is that the U.S. is working to stand up its own industry in the shadow of Canada’s over 20-year-old hemp sector, which has focused predominantly on grain production. The U.S. is “jumping into the Canadian market that’s been established,” said Bryan Parr, an agronomist with Legacy Hemp, a company that sells grain hemp seed and works with farmers in the Midwest and Upper Midwest. Due to the maturity of the Canadian market, U.S. farmers and processors in the grain sector experience significantly more stability, but also stiff competition from experienced operators to the north.

This report provides an introduction to the U.S. grain hemp market. We discuss the uses of hemp grain, or seeds; the estimated size of the market in the U.S.; and some practical and economic considerations of farming grain hemp, including production costs and prices for hemp grain. Finally, we relay the views of several experienced operators of how they see the market developing in the future.

Hemp Benchmarks 2020 Harvest Survey

Tell Us About Your 2020 Harvest!

(And enter to win a free Spot Price Index Report!)

This week we launched our 2020 Hemp Harvest Survey.

This survey aims to further identify the amount of hemp that has been planted and harvested for the 2020 season. If you’re involved in growing hemp for biomass, smokable flower, fiber or grain, please take 4 minutes to complete a short survey and help us better inform you.

We will be sending 10 randomly selected survey respondents a FREE copy of our November Hemp Spot Price Index Report that will be published on November 25th.

What is Grain Hemp?

In addition to producing cannabinoids and fibers, hemp is an oilseed crop, like flax, canola, or sunflower. Hemp seeds – or grain – are edible, highly nutritious, and contain omega-3 fatty acids, in addition to being high in protein.

Hemp grain can be pressed for edible oil; this oil is also employed in body care products such as soap. After being pressed for oil, the remaining material is referred to as hemp meal or cake. Hemp meal is high in protein and can be processed into flours and protein powders.

Inside the shells of hemp grain are hemp hearts, which are edible as-is, similar to the inside of sunflower seeds. Hemp hearts are also currently incorporated into food products such as granola and cereals.

Hemp grain and resulting products made from it have been given GRAS – Generally Recognized as Safe – status by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Chad Rosen of Victory Hemp Foods told Hemp Benchmarks that the FDA accepting the petition to designate hemp grain as GRAS was perhaps the biggest development to emerge out of the 2018 Farm Bill’s broader legalization of hemp for this sector of the industry. By contrast, FDA has not recognized CBD as GRAS and has stated that hemp-derived CBD cannot be added to foods, foreclosing potential markets for cannabinoid hemp.

There is also interest in using hemp grain as animal feed, but the FDA has not yet approved any products for such purposes.

How Big is the U.S. Grain Hemp Market?

At this time, any accounts of the size of the domestic grain hemp sector are estimates. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) told Hemp Benchmarks in an email that they do not yet have reliable data on acreage devoted to grain hemp production. Some state agriculture departments compile hemp acreage by end use, providing a partial picture of the scope of the market. However, a number of state agriculture departments lump grain hemp production in with hemp grown for seeds to be used for planting, further complicating the data.

As of October, data compiled by Hemp Benchmarks from state agriculture departments shows that there are about 13,500 acres licensed in the U.S. for production of hemp grain (or seed for planting) this year. About 10,000 of those acres were reported by the Montana Department of Agriculture alone. States where grain hemp is known to be grown – including North Dakota, Colorado, Kentucky, and Washington State – have not provided acreage figures, indicating that the total is likely a good bit higher.

Bryan Parr of Legacy Hemp speculated that the maximum amount of acreage planted with grain hemp nationwide is around 30,000 acres. According to a 2019 report on Canada’s hemp market from the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS), that figure is less than half the 77,800 acres that were planted in 2018 by farmers in our neighbor to the north, where grain hemp is grown primarily in the Prairie Provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba.

The FAS report on Canadian hemp states that yields can vary from about 1,000 pounds of grain per acre on dryland (22 bushels per acre on a 44-pound bushel) and up to 3,000 pounds per acre on irrigated fields. In Parr’s experience, yields in the U.S. are lower – for reasons that we detail below – with experienced farmers typically seeing about 1,000 to 1,200 pounds per acre, but sometimes as much as 2,000 pounds of hemp grain per acre. For those growing grain hemp for the first time, yields of 600 to 800 pounds per acre are typical.

In regard to revenue, a September report from Agri-Pulse quoted Roger Gussiaas, president of Healthy Oilseeds – a grain hemp processor in North Dakota – and Eric Steenstra, president of the advocacy organization Vote Hemp, as estimating the farm gate value for U.S. grain hemp production at between $14 and $15 million. Assuming a price of $0.50 per pound of seed, this would translate to 28 to 30 million pounds of hemp grain produced annually in the U.S. (We discuss reported prices for hemp grain in more detail below.) If average yields are around 1,000 pounds per acre, then the revenue estimates from Gussiaas and Steenstra indicate between 28,000 to 30,000 acres farmed for hemp grain in the U.S.

By comparison, the FAS report cited above states that Canada exported nearly 5,400 metric tons (about 11.9 million pounds) of hemp seed valued at almost $50 million, with over 70% of the country’s export volume going to the U.S. The export data does not capture processed hemp products (hemp hearts, hemp seed oil, hemp meal, etc.). Canada imported 726 metric tons (roughly 1.6 million pounds) of hemp seed in 2017, “mostly from the U.S.,” according to the FAS report, valued at $1 million. Of course, import and export figures do not capture the volume and value of the hemp grain that was produced, processed, and sold within Canada.

Farming Grain Hemp in the U.S.

According to our research, most of the domestically produced grain hemp comes from farmers in Montana and North Dakota. Minnesota officials reported about 1,900 acres registered as intended for grain hemp production this year. Reports from the field also state that grain hemp is grown in Washington, Colorado, Kentucky, Illinois, Indiana, and North Carolina.

Additionally, state agriculture officials in Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, and Texas told Hemp Benchmarks that acreage was registered for grain hemp this year, although each state apart from Texas reported only small amounts of production capacity, from only a few dozen to as many as about 125 acres. As always, licensed acreage does not always translate into planted and successfully harvested acreage.

The above overview shows that the states where most of the country’s grain hemp is grown are at higher latitudes. This is because most of the grain hemp cultivars on the market were developed in Canada and are adapted to the long day lengths experienced at more northerly latitudes.

This can present a challenge for farmers in the southern U.S., as the plants’ photoperiods will recognize the longer summer nights in those regions as signalling that the season is drawing to a close, with the result being premature flowering, lower yields, or even failed crops. Such a situation occurred this year in Texas. Calvin Trostle, Professor and Agronomist with Texas A&M University’s Agrilife Extension, relayed to Hemp Benchmarks that 500 acres of grain hemp consisting of three varieties – including the Canadian-developed X-59 – all went into reproductive growth within a month of planting in early May and ultimately failed. Bryan Parr of Legacy Hemp – who works extensively with the X-59 cultivar – stated to Hemp Benchmarks that he believes that Illinois and Indiana represent the southernmost states where Canadian-developed grain hemp varieties will be viable for commercial production in the U.S.

Parr also explained another reason that grain hemp has been adopted primarily in the Northern Plains and Upper Midwest: the approaches and equipment of farmers in those regions is better suited to grain hemp. Grain hemp “is very standard compared to what farmers [in those regions] are doing with other crops,” Parr said. Farmers in the aforementioned areas grow more specialty crops – such as flax, canola, and sunflowers, which are all also oilseed crops – compared to those in the Midwest Corn Belt, who primarily rotate corn and soybeans.

Furthermore, as an oilseed, grain hemp requires low-heat dryers to bring its moisture content down to a desired 9%. Such dryers are more commonly used for the other specialty oilseed crops mentioned above, so farmers growing those crops already have the appropriate dryers on hand. Farmers growing multiple specialty crops, as opposed to only corn and soybeans, also tend to have multiple grain bins, which facilitates proper storage.

In a recent episode of the Taking Root podcast, Gregg Gnecco of IND Hemp – a grain and fiber processor in Montana – pointed out that hemp grain is a food-ready crop and must be handled accordingly. Unlike other grains that are cooked as part of processing, hemp is not and so farmers must meet low microbial limits if a processor is to take their produce. In other words, having multiple separate bins allows farmers to keep their harvested hemp grain separate, clean, and marketable.

Wholesale Prices and the Economics of Growing Grain Hemp

Based on statements from Bryan Parr, Chad Rosen, and those contained in the Agri-Pulse article cited above, current prices for hemp grain are as follows:

- Non-organic / conventional: $0.40 – $0.55 per pound

- Organic: $0.95 – $1.15 per pound

Additionally, in the Taking Root podcast noted above, Gregg Gnecco stated that dryland hemp grain farmers can expect to gross anywhere from $500 to $800 per acre. Yields and gross revenue would presumably generally be higher for irrigated plots. While we noted earlier that Parr put typical yields in the 1,000 to 1,200 pounds per acre range for experienced U.S. farmers, he stated that good conditions this year led to some yields above 1,500 pounds per acre, while one farmer in west-central Minnesota saw 1,850 pounds per acre.

All of the sources with whom Hemp Benchmarks spoke emphasized that current prices for hemp grain are essentially set by the Canadian market. This creates challenges for American farmers as their Canadian counterparts enjoy advantages such as cultivars developed for their climates, the ability to use herbicides, and significant experience, all of which generally translate to higher yields and more efficient operations. Both Parr and Rosen also pointed out that there is excess hemp grain in storage in Canada, which pushes down prices and fills any supply gaps that may arise.

Due to ample supply and the fact that at the moment hemp seed food products remain a relatively small part of the markets for raw and processed foods, prices are reportedly fairly stable and are not susceptible to significant movement. Parr did state that he has seen a bit of a reduction, however, from roughly $0.60 to $0.65 per pound for non-organic hemp grain a year ago.

As noted above, Parr’s company – Legacy Hemp – sells seed to farmers. Parr stated that the going rate for grain hemp seed is $4 per pound and it takes roughly 30 pounds to seed an acre. He explained that such costs are another reason that grain hemp has gained a stronger footing in states such as Montana and North Dakota, rather than in Corn Belt states such as Iowa.

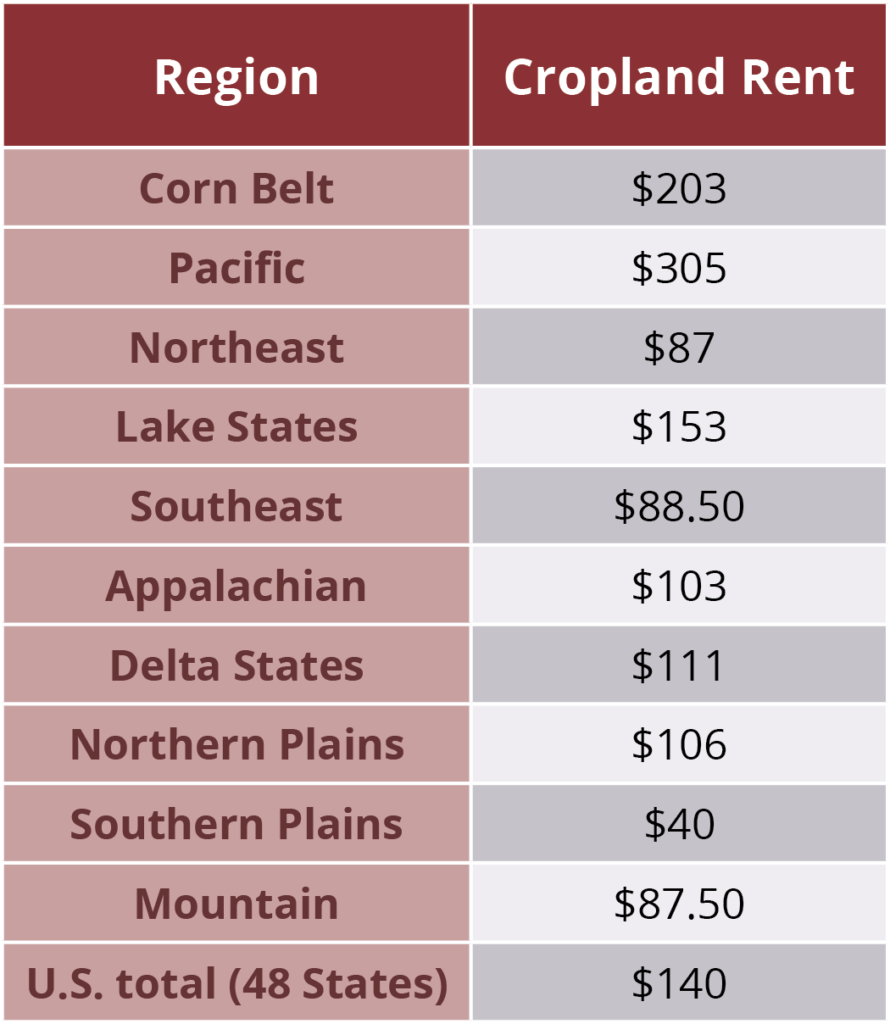

Annual data by region and State are available from QuickStats.

Parr pointed out that a hypothetical first-time grower who yields 800 pounds per acre and offloads the grain at $0.50 per pound will see a gross of $400 per acre. However, land rent in a state such as Iowa can run as high as $300 per acre, putting farmers in the red between that and seed costs alone, before any other expenses are even factored in, including state licensing fees and THC testing costs that are required of U.S. hemp farmers. In North Dakota, on the other hand, land rents are significantly lower – around $80 to $100 per acre, according to Parr – giving a farmer growing grain hemp more breathing room to turn a profit. The table on the right shows average land rent costs for different U.S. regions, according to the USDA.

It appears that organic cultivation of grain hemp provides an opportunity for American farmers. Tracy Rice – a New Mexico-based consultant and adviser for the grain and fiber sectors of the hemp industry – told Hemp Benchmarks in a recent interview that most of the hemp grain being produced in the U.S. is non-organic. Parr concurred and pointed out that organic farmers of other crops are generally profitable, thus they are not searching for new crops to add to their rotations, leading to lower adoption of hemp amongst organic growers. However, he stated that the demand for organic hemp grain is there and he does not see wholesale prices going down in the near future. Rosen also said that there is typically a shortage of organic hemp grain at the end of every season.

U.S. Grain Hemp Processing Landscape

The sources interviewed and consulted for this report stated that grain hemp processing facilities are operational in Montana, North Dakota, Colorado, Kentucky, and New York. We have identified IND Hemp in Montana, Healthy Oilseeds in North Dakota, and Victory Hemp Foods in Kentucky, as well as Evo Hemp in Colorado.

Processing capacity in the U.S. is not currently known. Rosen stated that Victory processes about 2,000 bushels of grain per month, which equates to roughly 1 million pounds per year. Parr stated that a processing operation in New York was purchasing 2 to 3 million pounds of hemp grain annually. Gnecco of IND Hemp stated in the podcast mentioned above that the company’s Montana oilseed facility was intended to support about 3,000 acres of production; assuming yields of 1,000 pounds per acre, this would suggest a processing capacity of 3 million pounds if fully operational. However, he also remarked that processing had ramped up incrementally after the facility opened in February 2019 and the buildout saw some delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The USDA FAS report cited above states that there were about a dozen hemp processors in Canada, and that over 700,000 pounds of U.S. hemp seed was exported to Canada in 2017. The report also states that Canadian processing companies “tend to contract hemp seed production directly with growers,” a situation that also appears to be predominant here in the U.S. Parr said that most grain hemp growers he knows have contracts and there is not much spot purchasing. However, Rosen did state that Victory does make some spot buys of hemp grain from farmers who grew it speculatively.

The Future of Hemp Grain in the U.S.

Rosen pointed out that the way consumers in the U.S. – and abroad – have been getting protein in their diets is shifting from animals to plants, an assertion buttressed by the recent rise of plant-based meat substitutes. This trend is also tied to a growing interest in sustainability, with the recognition that factory farming of livestock comes with massively detrimental environmental impacts. This combination of factors provides an opportunity for a sustainable, highly nutritious food crop such as grain hemp. For the hemp grain market to grow in the U.S., however, he said large CPG and food manufacturing companies – such as Unilever, Kraft, and Nabisco, to name a few – need to increasingly adopt and incorporate hemp seed and hemp seed-derived ingredients into their products.

To make that a reality, Rosen pointed out that hemp grain processors need to develop better “formats,” or different formulations of the oils, proteins, and other products derived from hemp seeds that can be easily slotted into the manufacturing operations of the large CPG companies. Rosen said that hemp grain processors should look to other oilseed ingredients that are used commonly in processed foods and how those ingredients have been developed to have certain characteristics – such as flavor, mouthfeel, how they emulsify, and other factors – that are desirable to food manufacturers, as well as companies producing body care products. If formats workable for the big CPG companies can be developed, then processing capacity will have to expand, he stated, as there is not enough currently online to meet significantly increased demand.

Animal feed is another potential large market for hemp grain, but it will take time to develop. The FDA is also in charge of approving ingredients for animal feed in the U.S. and Gnecco of IND Hemp pointed out in the Taking Root podcast that, prior to approval, separate trials must be conducted for each ingredient and each species, across an animal’s full life cycle. Overall, he said that the market for hemp grain to be used as animal feed is probably at least three to five years in the making. It should be noted that even in Canada, where grain hemp has been farmed for over 20 years, hemp and hemp products are not approved as livestock feed, according to the USDA FAS report.

At the farming level, the development of cultivars suitable to greater portions of the U.S. is something that will also take some time, but would allow American farmers to significantly increase production to meet potentially expanded demand. Along those lines, Tracy Rice asserted that she believes farmers need to be able to farm dual-purpose hemp crops that can be processed for both grain and fiber, which would make the endeavor more lucrative. However, she also noted that farming a dual-purpose crop typically results in sacrifices in yield, product quality, or both for the secondary production target. Calvin Trostle of Texas A&M gave the hypothetical example of a farmer harvesting hemp crops early for more supple fibers, which would result in immature seeds.

In addition to developing suitable cultivars, attaining successful dual-purpose farming of hemp for grain and fiber would likely require accompanying dual-purpose processing facilities to make production efficient, according to Rice, something that is rare in the U.S. currently. IND Hemp recently broke ground on a fiber processing facility to accompany its oilseed processing operation in Montana, but it is not expected to be operational until Q3 2021 at the earliest.

Overall, there is agreement in the industry that the development of the U.S. grain hemp sector will be a gradual process, as it has been to this point. For his part, Parr thinks it will remain a specialty crop grown largely in the regions where it is now being farmed, but he also said he could see greater adoption occurring in states such as Colorado and Nebraska in the future. Rosen suggested that farmers “stuck in the rut of row crops” should think about how grain hemp might fit into their rotations and start to “dip their toes” into growing small amounts in preparation for when increased demand might manifest.