In a relatively short period of time, since the national legalization of hemp and hemp-derived cannabinoids by the 2018 Farm Bill, there has been an avalanche of research and scientific studies regarding the scores of cannabinoids to be found in hemp and in cannabis sativa in general.

According to a report released in late 2020 by the Raymond James financial services firm, the biotechnology sector currently stands “at the perfect moment in history: a beautiful era of computational, mechanical, and biological technology convergence.” In terms of cannabinoids, the report continued, the sector’s ability to provide access “to pure, consistent, stable, and scalable sources of cannabinoids to large CPG [consumer packaged goods] and Pharma companies – beyond the ‘cottage industry’ that is cannabis today – could bring about a renewed wave of innovation and investment into bio-based technologies, not seen since biofuels.”

The report also estimates that the global market for products derived by cannabinoid biosynthesis could grow from $10 billion in 2025 to $115 billion by 2040. “Capturing even a small slice of 2040’s $115 billion cannabinoid biosynthesis product market,” it noted, “makes for a compelling investment case.”

Revolutionary Organic Chemistry

For Andrea Holmes, professor of organic chemistry and Director of Cannabis Studies at Doane University in Nebraska, the past several years have been breathtaking when it comes to the study of the so-called “major” and “minor” cannabinoids found in hemp. “In the last two-and-a-half years I have witnessed this explosion of new cannabinoids, whether it’s minor cannabinoids and isomers of THC,” she told Hemp Benchmarks. “I’ve never seen such an explosion of interest, and a hunger and desire to learn about these products.”

Holmes is also a partner and Chief Science Officer at CBD Remedies, a retailer of CBD and other hemp-derived cannabinoid products with three locations in Lincoln, Nebraska. The major change of the past several years, she noted, is “that we’re recognizing that cannabis is a pharmaceutical factory. It’s not just about CBD and THC; it’s about the precursors and all of the other isomers that can be [developed]. People are exploring new technologies, people are jumping into making little bio-factories to express minor cannabinoids. I mean, there’s like revolutionary organic chemistry, revolutionary biochemistry going on.”

Thinking in 3D

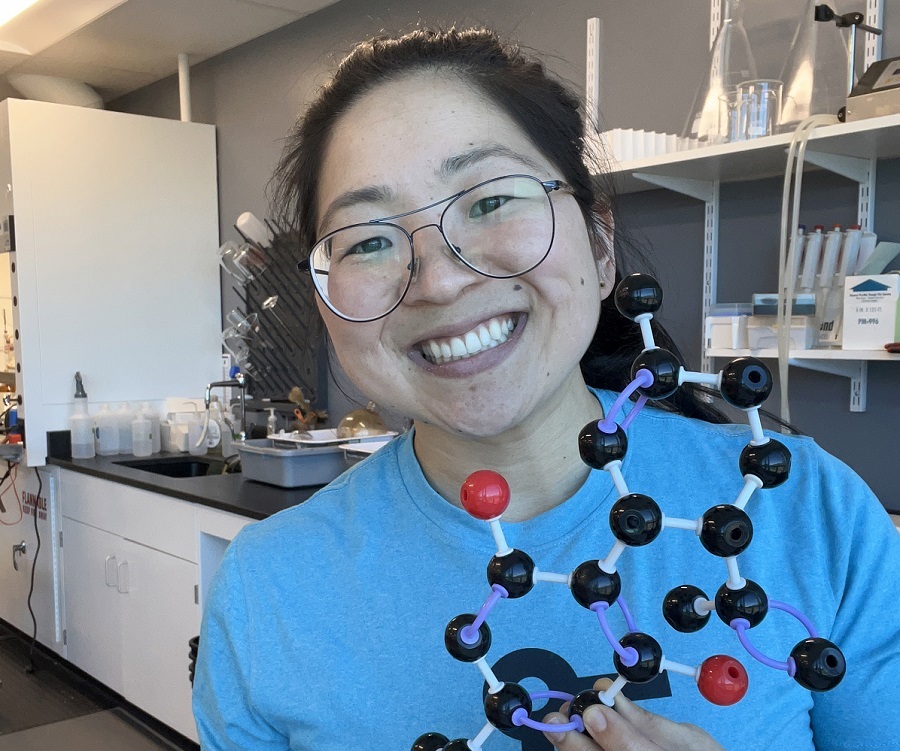

Miyabe Shields is Chief Scientific Officer at Real Isolates LLC, a research startup in Massachusetts that focuses on rare cannabinoids, specifically those created at high temperatures. They* noted that both consumers and hemp industry stakeholders are becoming more educated about hemp’s full potential, especially when it comes to manipulating the molecular structures of cannabinoids produced by the plant to synthesize new ones, as in the conversion of CBD to delta-8 THC and other compounds. [*Editor’s note: Dr. Shields uses the pronouns “they / them.”]

“My background is in pharmaceutical sciences, my Ph.D. is in the endocannabinoid system and in developing new molecules to target this system,” Shields told Hemp Benchmarks. The hemp plant, they said, “contains hundreds of molecules that are already structurally similar to ones that we know, that are active, that are non-toxic, and that can have many beneficial effects. So I think we’re at the tip of the iceberg.”

Both Holmes and Shields said cannabinoid researchers need to think three-dimensionally in order to imagine the intricate bonds and groupings found in these molecules, and how they give cannabinoids unique binding properties to certain receptors in the human endocannabinoid system.

As an example, Shields pointed to the chemical structure of cannabinol, or CBN. CBN is a mildly psychoactive cannabinoid that was discovered nearly a century ago and is only now being researched for its potential as a sleep aid. According to Shields, CBN is more chemically different from CBD than it is from THC. The difference, they said, is one single molecular bond. “There’s one bond that changes THC into a tricyclic molecule,” they continued. “From THC to CBN is only the loss of four hydrogen [bonds], specifically in the top ring. It’s almost identical to THC. It’s very, very similar.”

Tweaking Molecular Bonds

The tweaking of molecular bonds to create new products is not unique to cannabinoids; it has been successfully used for decades in pharmaceutical production. “This is nothing new,” said Holmes. “We stole a similar idea from the willow tree. Willow bark has salicylic acid. We take salicylic acid, and put an acetate group on it that helps with the way that aspirin works in the body. These methods are very common in the pharmaceutical industry to make the drugs more bioavailable.”

Shields noted that even minute changes in a cannabinoid molecule can create “really large changes, overall,” in a cannabinoid’s effects. They mentioned another cannabinoid: cannabigerol or CBG. “CBG is actually very different in structure from the other cannabinoids,” Shields said. “Because CBD has two rings in it, THC has three, but CBG only has one ring, with all these things kind of sticking out on the outside of it! It’s a really interesting molecule in terms of what it interacts with. It appears to have a very different pharmacology. CBG is somewhere in between THC and CBD In its qualitative effects, but there are things that haven’t been verified.”

Given the newness of this research, there are still unanswered questions regarding whether the rarer cannabinoids can be produced in quantities that would make them cost effective. “It depends,” said Holmes. “CBD, for example, you can buy for a couple of hundred bucks per kilo. You can’t make it cheaper with synthesis.” However, she noted, more refined breeding techniques might make a difference, with some researchers looking at how they can develop hemp cultivars that might express more of these minor cannabinoids.

Preparing for New Discoveries

Shields added that the study of hemp cannabinoids has benefited from decades of trial-and-error work that took place outside of formal scientific study, before legalization. “We have tons of information from people, and not in clinical settings,” they said. “But that doesn’t mean that that information isn’t valuable. And that’s what I’m starting to get really excited about with the rare cannabinoids.”

“We are at the brink of amazing discoveries,” said Holmes. “We’re at the brink of opening an area of pharmaceutical and clinical research opportunities, we’re at the brink of exploiting molecules that can be found in nature that can actually change the landscape of medicine, how medicine is being practiced, and how the health and wellness markets can be shaped in the future with functional foods and beverages and nutraceuticals.”